Prerelease:The Sims (Windows)/1995-1996

This is a sub-page of Prerelease:The Sims (Windows).

Contents

Dollhouse Demo at Stanford

| "Imagine zooming into SimCity 2000, all the way down to the street level, and seeing little people walking around, waving at each other, asking for spare change, jumping up and down, gesturing, interacting with each other, living and playing in rooms with furniture and active objects, and you're one of them! Will showed me Dollhouse several years ago, and it was amazing then, and even more so now. It's not a product yet, but he's been working on solving some very hard problems. He's trying to give the people who walk around the world seemingly rational behavior." |

In April 1996, Will Wright gave an insightful talk on Interfacing to Microworlds for a User Interface class held by professor of computer science Terry Winograd at Stanford[1][2][3][4][footnote 1]. The original direction of the talk was the building of a reflection, along the audience of students/enthusiasts, about the strengths and weaknesses in the sense of the user-friendliness, replay factor and creative boundaries in previous efforts by his team at Maxis — most precisely SimCity 2000, SimAnt and SimEarth. Towards the end of the talk, an open Q&A session was done with many interesting questions by the people there at the class[1][2].

The one who caught Wright by (a good) surprise, however, was the one guest that raised their hand and, out of civil curiosity, inquired the Maxis co-founder about the projects that he was working on at that moment[footnote 2].

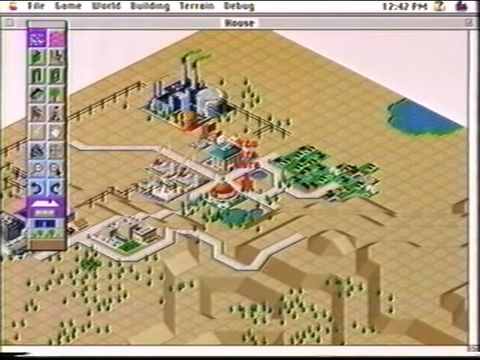

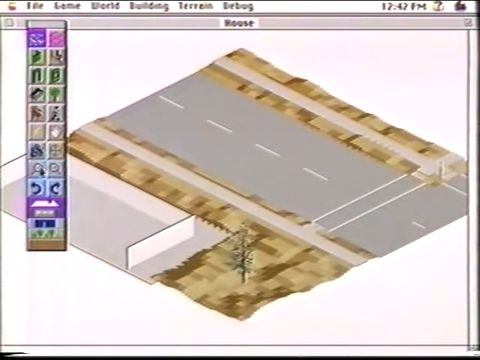

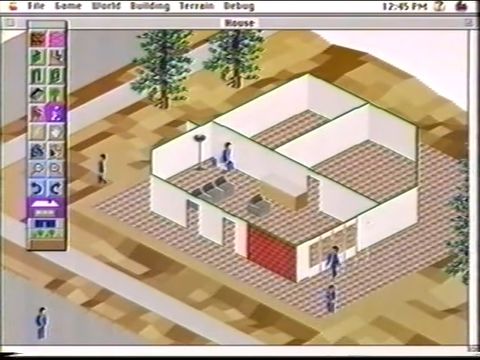

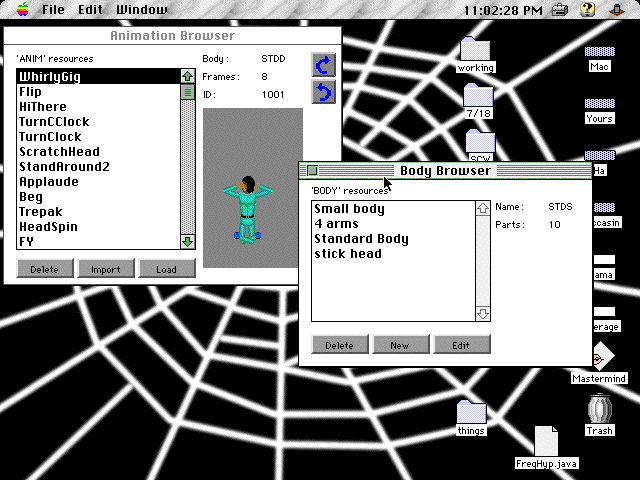

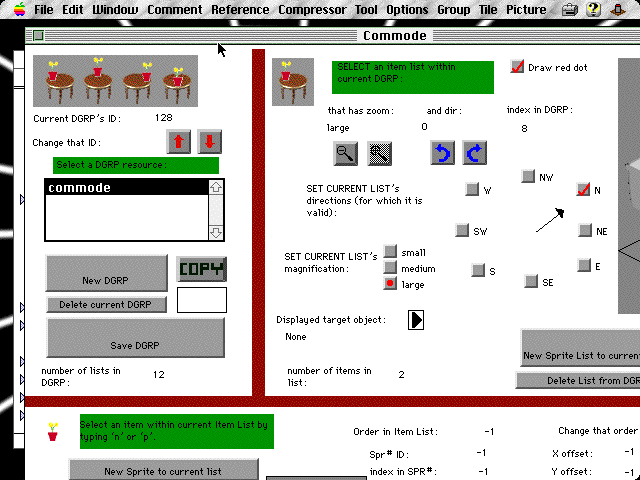

The mood of the seminar was increased from the moment that, influenced by that question, Wright commands his Macintosh to run what appears to be a slightly modified copy of SimCity 2000, this time allowing the player to see what was happening inside the buildings' walls and who lived in there...

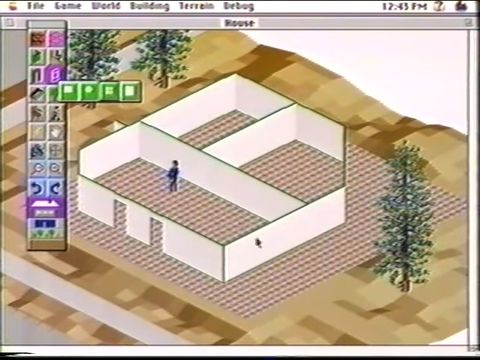

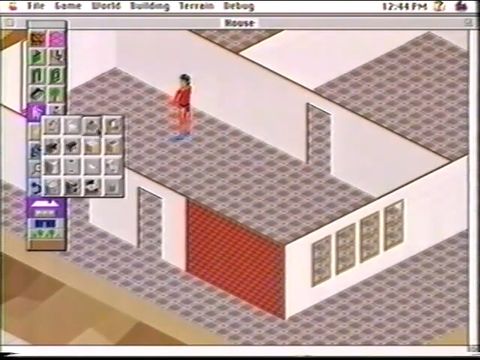

Described as "a CAD program that a 10 year old could use", Wright goes ahead and tours a working, but extremely early draft of The Sims (yet, still titled as Dollhouse) to a public that very well knew when to stare out of fascination, and laugh at the first vision of a Wright-like rag doll perpetually sitting on a toilet.

At first, it all seems to be an ordinary SimCity campaign...

If Project X's biggest challenge was to have its perception expanded to something more complex than being summarized as a "game you have to use the toilet", that is precisely what invoked the smiles among the spectators that day, at Stanford.

Noteworthy Details

- This far ahead in development, Wright already envisions Dollhouse as a "hobby" more than uses "game" to describe his new project, and that's because he was already looking for ways of combining the characteristic open-endedness from his previous works with the possibility of making it viable for players to expand indefinitely and exchange their own resources and stories with other people online — and it's absolutely no coincidence that, in the following years, it would be precisely the strong potential of storytelling and the building of communities of players that made executives at Electronic Arts as Luc Barthelet to think highly of The Sims more than many of those at Maxis.

Jamie Doornbos on Dollhouse

| "I first saw what would later become the Sims as a prototype Will Wright was working on. This was in the summer of 1995, when we were pitching Will on our new game and company. He heard us out, gave us great advice, and then showed us his cool prototype (very much like Will overall). He had a little man (graphically made out of animated, unconnected rods) walking around a gridded floor space. Will wanted to show us something he'd just completed: he dropped a toilet onto the grid, and the man went over to it, sat down on it, and then after a moment got up (complete with flushing sound if memory serves me correctly). Very funny, and it gave a glimmer of what the Sims would become. The ability to have the animations needed to use an object bound to the object rather than in the Sim was in fact an important internal feature of the game." |

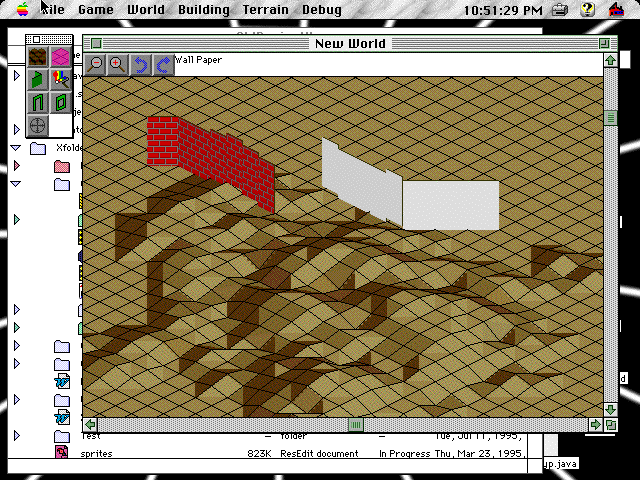

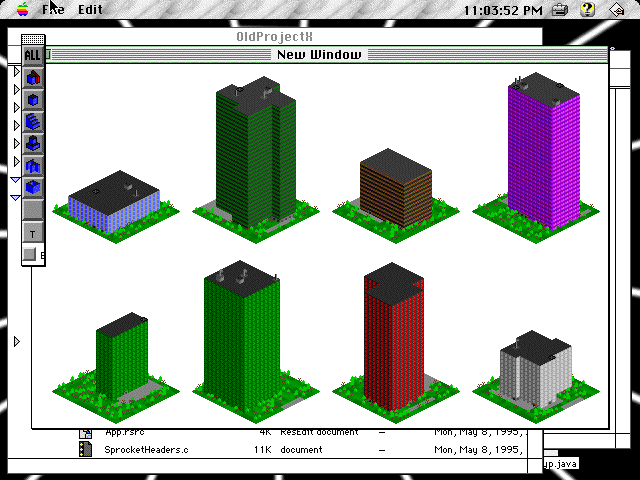

As a secret side-project, The Sims productive momentum gradually increased when Wright tapped an ambitious Jamie Doornbos — a God-game enthusiast who had just graduated from Stanford — , to ensure his vision would be manifested with the highest precision[6]; in fact, Doornbos wrote the first known code for the game, as his fellow Maxoid Jacquin Servin was committed to the original character animation engine[7] until... you know, something hit the propeller.

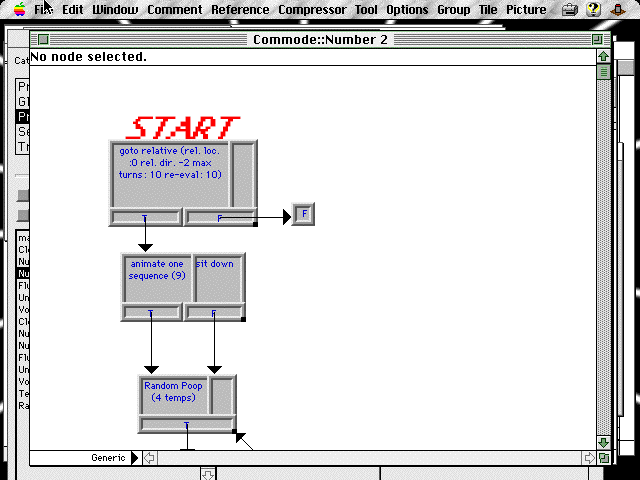

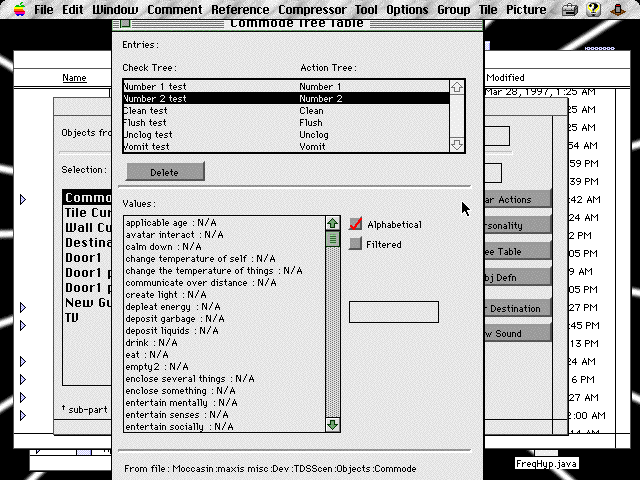

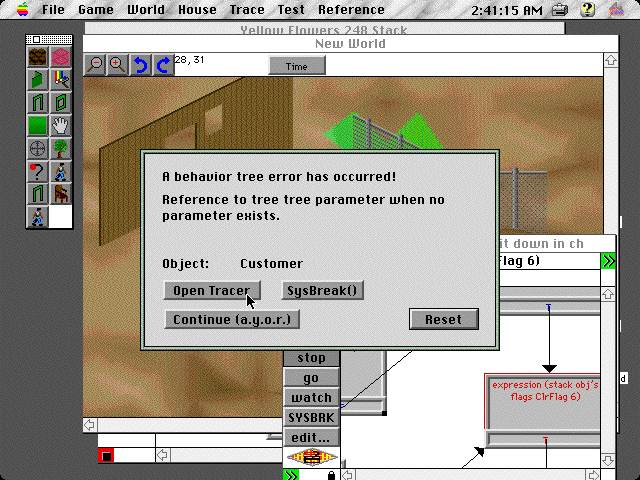

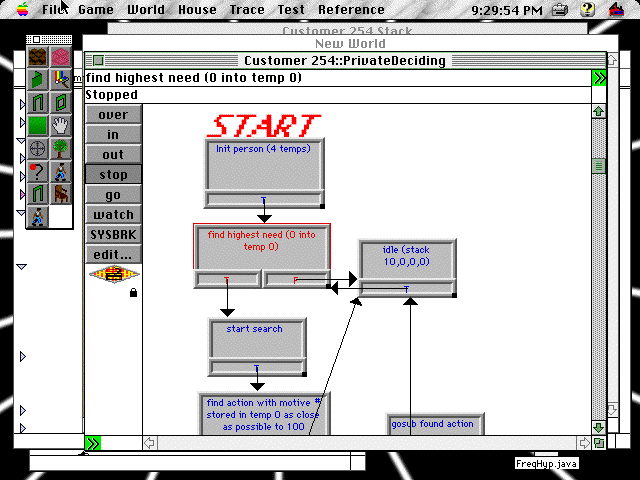

It was starting to look like something, after all! Its was first targeted for the Macintosh, and provided a very small, but fundamental basis for SimAntics, the visual programming language that orchestrates the Sims' behaviors with ObjMaker (Edith's precursor) as its editor. While rudimentary, it had some use during the engineering of the intelligence from the own Sims of SimCopter, being one (but definitely not the only!) times when the stars from a work make an early debut.

Below is the comprehensive print of Doornbos' lost documentation on Project X, published at his old blog nearly one month after the first public launch of the game.

Footnotes

- ↑ Among the attendees, a then-member of the Interval Research Corporation, one Don Hopkins: a user interface aficionado who "performed empirical pie menu experiments to prove they're faster and more reliable than linear menus". Through fate or luck, Hopkins is introduced to Doornbos anyways, along with programmer Eric Bowman, by Jim Mackraz at the Game Developers Conference '96, where he is recruited to join Maxis and work on Will Wright's team. Whatever graphical and behavioral improvements that Doll House met over this short gap of time, the recently finished social part of the simulation, plus the intuitive architecture that had been part of the project since the beginning, changed the minds of Maxis' Core Technology Group, convincing them to dedicate time and resources to the dream that was Project X.

- ↑ What projects are you working on now, and if you’d rather not talk about that, what projects or models had you considered before that were kind of interesting that you didn’t do?

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Designing User Interfaces to Simulation Games, Don Hopkins (January 12nd, 2004)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Designing User Interfaces to Simulation Games, Don Hopkins (Medium, 2023 Revision)

- ↑ Interfacing to Microworlds, Will Wright, Maxis - SearchWords - Stanford Library

- ↑ Interfacing to Microworlds ,April 26, 1996 - Brief

- ↑ Mike Sellers, Quora, 2016

- ↑ Meet The Sims (Carly Berwick, METROPOLIS, January 2000)

- ↑ Eric Bowman, Quora, 2016